Transfer of print from paper to emulsion - medium format

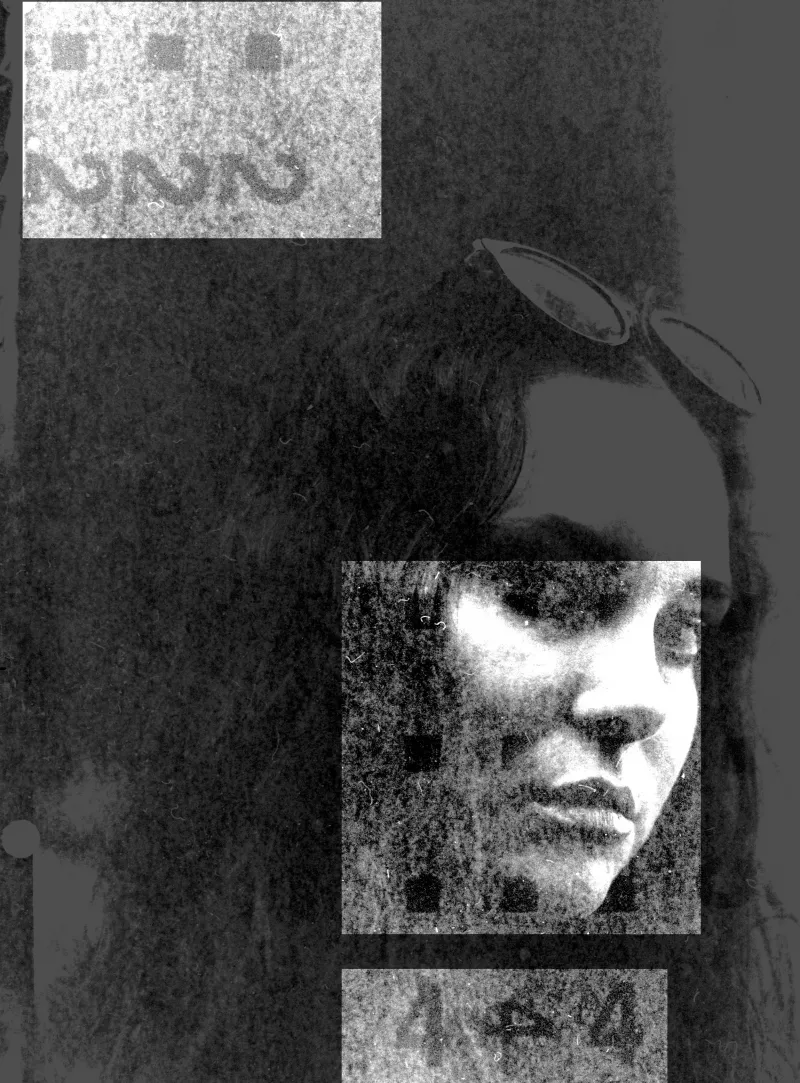

Strange symbols, squares, and dots on the developed film.

Today is going to be a bit technical – I've returned to the darkroom. Five rolls of 120 film is quite a lot, so an intense day was ahead: sleeves rolled up, developing tanks ready, chemicals at the perfect temperature. The material was carefully selected – ISO 100 for outdoor shots in full sunlight, ISO 400 for interiors and deep shadows, ISO 200 for places where the light was diffused, soft, and subtle. Everything black and white, everything thought out almost textbook-like – I wanted to maximize my chances of getting strong, technically correct frames.

And then disaster struck.

I completely forgot that these ISO 200 rolls were quite old. I had bought them once with the idea of testing some medium format body – it didn't impress me, and the films, instead of being stored in the fridge, ended up somewhere aside. They lay there for years, forgotten, because they didn't bother anyone. Unfortunately, time and storage conditions took their toll.

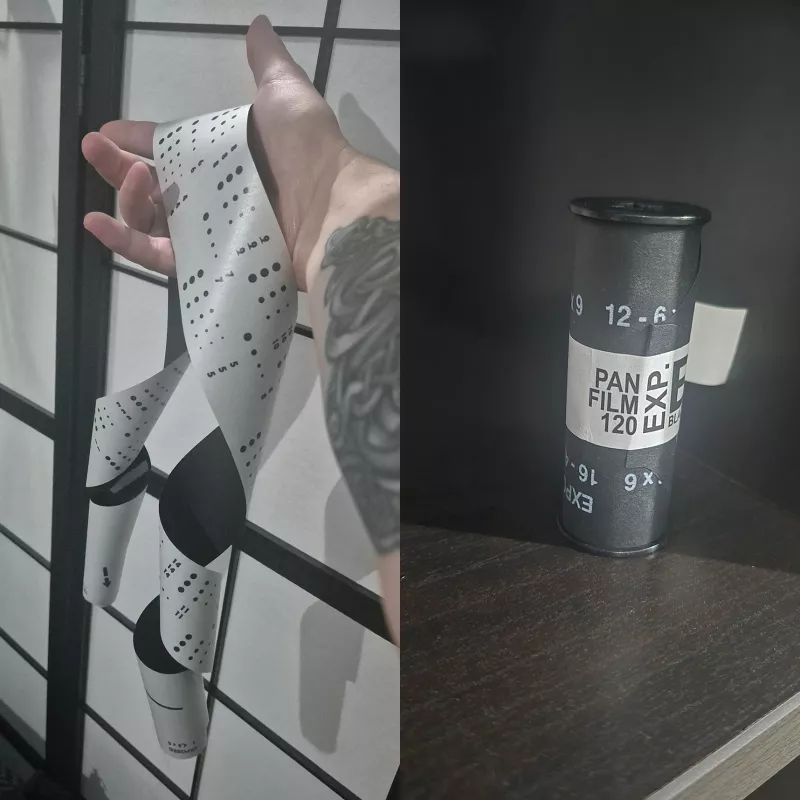

Medium format film 120 construction

Unlike large format sheets (where there is no protection) or 35mm films (type 135), which are enclosed in a sealed canister, medium format films have a completely different construction and packaging method. They are wound onto an open spool without any additional casing, and to prevent accidental exposure, they are protected by black backing paper. This element sometimes turns out to be the Achilles' heel of the entire construction.

This paper is covered with characteristic patterns – it must be compatible with various formats and cameras, including older ones that do not have a mechanical frame counter. Therefore, it features various markings: numbers, dots, squares, arrows. These signs were meant to be helpful – they allowed users to precisely position the film in the viewing window located on the back of many older cameras.

Typically, backing paper (the protective paper for medium format film) has two distinctly different sides – the side facing the emulsion is black and matte, designed to minimize light penetration and not reflect it towards the film. The outer side – the one the photographer sees through the camera's window – is also black, but often has white printing (numbers, symbols, control marks), or vice versa: light with dark markings. The key is that all information is clearly visible even in difficult lighting conditions.

The concept of a frame counter in a medium format camera.

To maintain an educational value, I will now show an example of how the back cover of an old Agfa Billy camera looks. You can see the characteristic red window on it, through which we read the frame number directly from the backing paper. The number 4 is visible in the photo, which means the film has been wound to the fourth frame. If I were to turn the knob further now, the number would change to 5, and the film would advance by another few centimeters. Simple and effective – this is how the frame counter issue was solved without the need for complex, precise mechanisms.

However, the situation becomes complicated when we consider that "medium format" actually refers to several different formats. The most popular are 6×4.5, 6×6, 6×7, 6×9, or even 6×12. Each of these has a different frame size, which means the film must be wound to different lengths. That's why on the backing paper, you will find several rows of numbering – one for each format. In a 6×6 type camera, you will use one row of numbers, in a 6×9 another. It's a bit confusing, but if you've come here, you're probably looking for an answer to a specific problem – and you already know what it's about.

What happened then?

And here we reach the end of this story – let’s try to answer it ourselves.

The imprint from the backing paper, over time, temperature, and according to some sources, also humidity, gradually transferred onto the photosensitive emulsion. Instead of being just a superficial trace, it became an integral part of the image – fixed just like any other part of the frame.

When I first looked at the film after developing, I couldn’t understand what had happened. I thought it might be just ordinary dirt – maybe the imprint could be washed off, wiped away? But no. Those numbers, symbols, and lines were no longer a print. They had been... photographed. They were in the image.

Having five rolls to compare, I quickly identified the culprit – ISO 200. The roll I bought a few years earlier "for trial," and then forgot. I noticed that the film had a different color – it was slightly yellowish. Maybe also slightly sticky, although that could have been a subjective feeling (wet films often give a similar impression).

In short – a phenomenon similar to contact printing occurred here. The contact between the emulsion and the imprint was long-lasting, almost immobile. The transfer was slow but effective. Years did their work, and the entire content of the backing paper "imprinted" on the film frames.

I don’t know exactly how this happens. Is it a photochemical reaction? Purely chemical? Or maybe the material was exposed to some radiation? Hard to say. But the effect is irreversible.

How to prevent it?

After this lesson, I read up, dug into sources, and gathered a few simple rules – to simplify your research:

-

Store the film in a cool, dry place – preferably in a refrigerator. Darkness and low temperature significantly slow down chemical processes.

-

Don’t leave a loaded film in the camera for too long – especially if the photos are already taken and the film is waiting to be developed. The contact between the emulsion and the imprint lasts the longest then.

-

Avoid humidity – if you live in a place with high humidity, store films in airtight containers with a moisture absorber.

-

Develop the film as soon as possible after exposure – the shorter the film waits, the less risk there is that the emulsion will absorb something it shouldn’t.

Why is it worth storing films in the refrigerator?

Storing photographic films in the refrigerator significantly slows down the chemical processes that eventually lead to the degradation of the emulsion. At lower temperatures:

-

the emulsion remains stable and less susceptible to moisture or heat,

-

unwanted effects, such as backing paper transfer, are avoided,

-

the film retains its photosensitive properties longer — particularly important for expired or rare films.

Low temperature acts as a natural "preservative" for photosensitive material, which is why storing films in the refrigerator is the simplest and most effective way to protect them from quality loss — both before and after loading them into the camera.

It is enough to keep them in an airtight container (e.g., a plastic box with a lid and a moisture-absorbing sachet) to avoid water condensation and ensure stable conditions.

Sometimes expired films are desirable — especially among enthusiasts of the lo-fi/lomography aesthetic, experimentation, and surprising results. This is particularly true for color 35mm films, which can develop a completely new character over time. Changes in the emulsion lead to color shifts, increased grain, unusual tonality, and even completely unpredictable, psychedelic effects. For many photographers, this element of randomness becomes the greatest asset — an invitation to a creative play with photosensitive materials.

However, the situation is entirely different when it comes to medium format. Here, most photographers use film not to achieve strange colors or random discolorations but to work consciously with image plasticity, detail richness, and tonal depth. Medium format means precision, not chaos. Meanwhile, expired 120 film rarely rewards aesthetic courage — it more often punishes it with technical imperfections. Backing paper marks, uneven photosensitivity, significantly degraded image quality, or color instability can turn an artistic experiment into simply damaged material.

It's hard to find a rational justification for deliberately shooting with expired medium format film unless someone does it fully consciously, with a clear aesthetic intention — and accepts the risk that no frame will survive the process unscathed. In practice, while a "mistake" in small format can be a value, in medium format, it too often becomes just a problem.

Dominika Swr

The photo features the incredibly photogenic and talented Photographer — Dominika SWR. You can admire her exceptional works on Instagram, among other places. She is a fascinating figure who navigates both in front of and behind the lens with equal ease.

Dominika SWR is someone who always leaves a pleasant sense of wanting more — the kind that makes you crave more. I follow her work with genuine fascination because each time she brings something valuable: an image, a word, a gesture. And when she stands in front of my lens and allows me to be part of that moment, I feel pleasantly honored.